Jared Homola, PHD Student, University of Maine

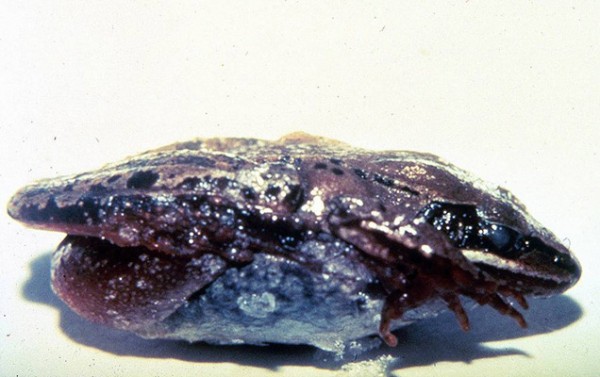

As the days get shorter and temperatures dip, much of the natural world is undergoing seasonal rites of passage in preparation for the often-challenging winter. For instance, some small mammals will lower their metabolic rates during the winter, allowing them to survive during these months of relatively little forage. The black bear, a species especially beloved here at UMaine, uses the same strategy to survive our long, cold New England winters. As impressive as this type of hibernation is, wood frogs use an even more astounding strategy to survive the cold—allowing up to 65% of their bodies to turn to ice. While frozen, wood frogs experience many unique processes. For instance, their hearts stop beating, consequently stopping their circulatory systems from functioning, effectively making them dead by conventional definitions. However, during this time, individual cells continue to function, albeit without the communication between them that typically exists. Once warmer temperatures arrive in the spring time, the wood frogs thaw and their hearts slowly resume their normal rhythms just in time for their annual migrations to nearby vernal pools.

Several recent research projects have sought to better understand the ability of wood frogs to freeze. Sullivan et al. (2015) recently identified a gene, fr47, which appears to allow freezing to occur. Using an analysis of gene expression, the researchers found that the gene was activated in various tissues throughout wood frogs in response to freezing, allowing the frogs to survive dehydration and oxygen deprivation. Another recent study by O’Connor and Rittenhouse (2016) indicated that the ability of wood frogs to successfully complete their winter survival transformation is related to the amount of insulating snow cover that exists, as well as how deep a frog is able to burrow into its winter hibernacula. As climate change continues to redistribute snowfall, the wood frogs that live in locations that end up with relatively less winter precipitation are likely to suffer.

References

O’Connor, J.H. and T.A.G. Rittenhouse. 2016. Snow cover and late fall movement influence wood frog survival during an unusually cold winter. Oecologia.

Sullivan, K.J., K.K. Biggar, and K.B. Storey. 2015. Expression and characterization of the novel gene fr47 during freezing in the wood frog, Rana sylvatica. Biochemistry Research International.